With negotiations in Copenhagen only days away, healthcare insurance reform under active discussion, and cap and trade legislation the next big ticket item on the U.S. Congressional agenda, it seems appropriate timing to broaden the climate change debate to include its public health consequences.

Global authorities such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have identified climate change as a significant emerging threat to public health worldwide.

Why?

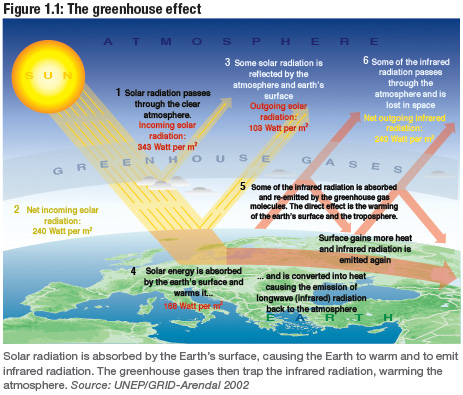

Climate scientists have found that Global Warming, the tendency of the Earth to warm when certain gases accumulating in the atmosphere prevent solar radiation from escaping out to space after bouncing off of the Earth’s surface, will cause (and has probably already started causing) increased temperature and increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as hurricanes, drought, extreme heat, and flooding.

2009 Climate Change Science Compendium. Ed. Catherine P. McMullen. UNEP, September 2009. Figure 1.1. p. 4.

The following table, "Anticipated Health Effects of Climate Change in the United States,” adapted from Frumkin et al., Am J Public Health (2008); 98:435-445, outlines the likely health effects and associated vulnerable populations associated with a changing climate.

|

Weather Event |

Health Effects |

Populations Most Affected |

|

Heat waves |

Heat stress |

Very old Athletes Socially isolated Poor Respiratory disease |

|

Extreme weather events |

Injuries Drowning Mass population movement International conflict Mental health |

Coastal, low-lying land Poor Children Displaced Depression/anxiety General population |

|

Winter weather anomalies |

Slips and falls Motor vehicle crashes |

Northern climate dwellers Elderly Drivers |

|

Sea-level rise |

Injuries Drowning Water and soil salinization Ecosystem disruption Economic disruption |

Coastal dwellers Low SES |

|

Increased ozone and pollen formation |

Respiratory disease exacerbation (e.g. COPD, asthma, allergic rhinitis, bronchitis) |

Elderly Children Respiratory disease |

|

Drought – ecosystem migration |

Food and water shortages Malnutrition |

Low SES Elderly Children |

|

Drought, flooding, increased mean temperature |

Food- and waterborne disease Vector-borne disease |

Swimmers Outdoor workers Outdoor recreation Poor Multiple other populations |

So, why is public health largely excluded from climate change policy?

Climate change policies such as the Kyoto Protocol and non-binding challenges such as U.S. Council of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement have focused largely on encouraging energy efficiency measures and boosting renewable energy capacity for two reasons:

1. They appear to directly address the problem: too many human-generated greenhouse gas emissions; and,

2. They reduce a complex, global crisis into a two, easily digestible strategies.

The problem with this strategy has been that it robs the climate change crisis of immediacy. The average person or company does not “see” the tangible benefits of reducing energy consumption and purchasing renewable energy. Their small contribution will not change the world’s climate in a readily noticeable way, and it probably will not even change the microclimate around an individual house or business unless the activity is coordinated into a neighborhood or district level, as advocated by the Living Building Challenge through the concept of “Scale Jumping.”[1]

Energy efficiency saves money up front to a point, but the cost-benefit analysis for an energy efficiency strategy loses its appeal after the obvious measures have been implemented (e.g., changing to energy efficient light bulbs, etc.) – unless another value proposition is overlaid that brings immediacy and another order of magnitude to the enterprise.

This column will tease out that value proposition by uncovering the links between public health and climate change policies and practices. It will place particular emphasis on economic co-benefits and the power of a health message to build political will and influence behavioral change.

Copyright: © Biositu, LLC, and Building Public Health, 2010.

[1] “Scale Jumping” is defined by the Living Building Challenge as “the implementation of solutions beyond the building scale that maximize ecological benefit while maintaining self-sufficiency at the city block, neighborhood, or community scale.” Source: http://ilbi.org/the-standard/lbc-v1.3.pdf, footnote 14, p. 11.