Environmental sustainability often appears totally unrelated to the day to day work of a public health official. In many cases, the new technologies touted to reduce energy and water use, encourage composting and recycling, and reduce exposure to potentially harmful emissions in building materials and housekeeping chemicals raise questions. Do they meet regulatory standards for sanitation? Do tests that work on conventional technology apply to these new systems? Do they straddle regulatory jurisdictions?

This column will argue that environmental sustainability lies at the heart of environmental public health. In fact, the tension between the public health benefits of access to clean water and green space and the public health concerns associated with suburban sprawl (e.g., social isolation, obesity, cardiovascular health, respiratory health, stress, etc.) dates back to the formation of the public health industry in the 18th century.

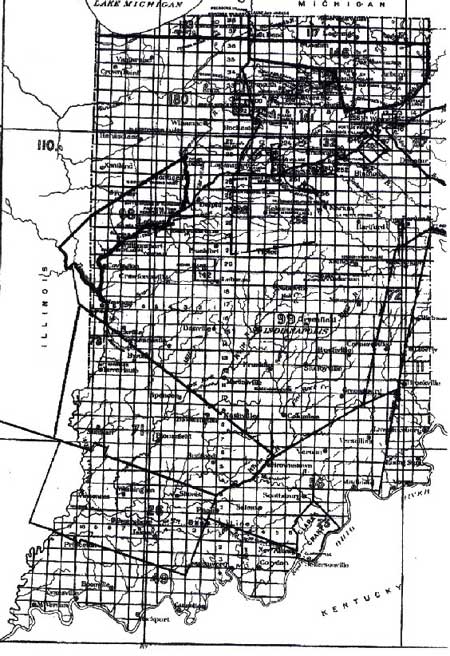

Jeffersonian Grid: Plotting the Frontier

The origins of land planning and urbanization in the U.S. can be traced to the Land Ordinance of 1785, an arbitrary grid composed of “sections,” each measuring one square mile (or 640 acres), which was projected across the entire North American landmass west of the thirteen original colonies. This division of land is also called the “Jeffersonian Grid,” because Thomas Jefferson proposed the idea as a mechanism to preserve the agrarian lifestyle of the ex-colonies while providing adequate land to all voting citizens. Each citizen was to receive one section of land (640 acres), an acreage calculated by Jefferson as ample to provide for a farming family.

Figure 1: Indiana Land Survey (source: Carl Leiter)

The Jeffersonian grid encouraged Western expansion by subdividing a largely uncharted wilderness into legally defined parcels of land with potential future value. The government opened the majority of vacant land up for sale while retaining the future value of specific sections in each township to support government services such as free public education. [1] The unique relationship between government and landowners in the U.S. can largely be traced to this initial attempt to raise public funds.

The Origins of Public Health Policy: 18th and 19th Century London

In 1785, the same year as the passage of the U.S. Land Ordinance, a movement was gaining momentum in Great Britain that set the foundation for modern public health policies by using the new science of epidemiology to establish a correlation between disease and mortality rates and rapid urbanization. Oddly enough, engineers and urban planners, not doctors, were given the responsibility to improve public health statistics (such as the mortality rate) in urban areas.

The speed of urbanization in this period outstripped the construction industry’s ability to provide proper housing conditions, particularly in London. Urbanization progressed so rapidly that the demographics of the country reversed within a century. In 1801, only 30% of the population of England and Wales lived in urban areas with a minimum of 2,500 people. By 1901, that number had reversed; 70% of the population lived in urban areas. A similar, although not as dramatic, demographic shift occurred in the U.S. during the same period. [2]

Utilitarianism [3], a philosophical movement derived from the Enlightenment, gained popularity in the U.K. in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as a method for improving the overall productivity of the poorer urban populations that were most affected by rapid urbanization. The Utilitarian project conformed to the miasmic theory (the belief that disease was caused by “miasma,” or a poisonous vapor) that disease could be eradicated from urban slums by removing its supposed cause: poor public hygiene and overcrowded housing.

By employing engineers and urban planners to implement Utilitarian concepts, the first public health policies in the U.K. established a distinction between public and private health. Public health was designated as the realm of preventative measures (the engineer’s expertise) and placed in a separate sphere from curative medicine (the doctor’s expertise). Engineers and urban planners spearheaded public health projects such as providing access to clean water, building sanitary sewers, paving roads, and improving access to light in previously overcrowded neighborhoods. Similarly, the first national General Board of Health, established in the U.K. through the Public Health Act of 1848, was dominated by engineers.

Public Health Today

Gradually, through the 19th and 20th centuries, as utility infrastructures improved, the affects of infectious disease outbreaks lessened, and the average American lifespan lengthened, the importance of public health was eclipsed by the medical industry and a growing focus on private health. Today, few doctors are trained to identify and diagnose medical conditions arising out of the patient’s physical surroundings.

And yet, our surroundings largely determine our level of physical activity, our exposure to environmental hazards such as air pollution, and our level of personal interaction. A growing body of research identifies post-war suburban land use in particular as an influential contributor to the chronic diseases that are filling hospital emergency departments and driving up the cost of health insurance. Significantly, many local public health departments interested in engaging in environmental sustainability activities have returned to their roots by offering their expertise to local and regional planning departments that, throughout the 20th century, had focused almost exclusively on the calculated economic and environmental impacts of potential developments and taking their public health consequences for granted.

This column will map out specific examples of linkages between areas of concern within the traditional public health model (i.e., food safety, air quality, solid waste, vector-borne diseases, water and wastewater, etc.) and efforts in environmental sustainability.

The public health industry offers a wealth of science-based experience and expertise waiting to be tapped in the interest of advancing human health, community health, environmental health, and economic health. The case studies, reports, tools, and resources outlined in this column will begin to develop a framework for an enhanced public health identity that includes active engagement and leadership in environmental sustainability.

Copyright: © Biositu, LLC, and Building Public Health, 2010.

[1] “Land Ordinance of 1785,” Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Land_Ordinance_of_1785

[2] From 1831 to 1892, the U.S. population changed from one in ten residing in cities to one in four. However, much of population growth during that period of time was due to immigration. From 1850 to 1900, U.S. population grew from 23 million to 76 million inhabitants, most of whom were newly arrived immigrants. Witold Rybczynski, City Life: Urban Expectations in a New World, Scribner: New York, 1995, p. 111, 115.

[3] Information on Utilitarianism and “the sanitary idea” taken from: Graham Mooney, “The Sanitary Idea” lecture, History of Public Health course, Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, http://ocw.jhsph.edu/courses/HistoryPublicHealth/lectureNotes.cfm