Scrambling Climate Change Categories: Understanding the Public Health and Sustainability Co-Benefits of Crossing Adaptation and Mitigation Boundaries (part 1 of 3)

Categories fill an important role in the development of new fields of study. They set a framework for understanding new ideas. They inform priorities for research and innovation. And, they encourage engagement with complicated concepts by attaching a “short hand” label to topics that might otherwise only be discussed in academic or scientific circles.

Scientific and political authorities have developed two such categories, or labels, to distinguish between policy responses to climate change.

Adaptation refers to activities that reduce vulnerability to the projected short- and long-term impacts of climate change.

Mitigation refers to activities that reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, thereby working to slow (and eventually stop) global warming.

Public health and sustainability have traditionally identified with different climate change categories: public health participating in adaptation activities and sustainability focusing on mitigation technologies and strategies.

This series of three blog posts will review the traditional role of public health (part 1) and sustainability (part 2) in climate change activities before proposing that both disciplines would be better served by collaboratively engaging across categories—combining adaptation with mitigation (part 3).

The following adaptation activities fall within the traditional role of Public Health:

1. Establish a formal interagency mechanism to identify and prioritize potential risks to human, natural, and economic systems resulting from climate change. Support vulnerable communities’ adaption to these changes.

Link to Public Health

Certain populations are particularly at risk to the public health consequences of climate change. Public Health can help identify vulnerable populations and target preparedness and emergency response activities to reduce vulnerability and increase resilience.

Sample Locations

Alaska

Health and Culture Adaptation Options, September 2009, HC15: Office of Climate Change Coordination (link)

Arizona

Establish a state adaptation advisory group (link)

California

Climate Adaptation Advisory Panel (link)

California, 2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Public health strategy 7 (link)

Florida

Energy and Climate Change Action Plan: Phase 2, 2008, GP-3: Inter-Government Planning Coordination and Assistance and ADP-13: Coordination with Other Regulatory and Standards Entities (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation C.3, D.10, E.4, F.3, F.4 (link)

2. Increase surveillance of infectious and non-infectious diseases associated with climate change.

Link to Public Health

A public health surveillance infrastructure already exists at the state level and, to some extent, at the local level. The CDC launched a National Environmental Public Health Tracking Network in 2009 to coordinate activities at the state and local level and start building a national surveillance program.

Depending on the location, climate change could be linked to diseases associated with:

-

changes in the season and range of vectors (e.g., mosquitoes);

-

sanitation concerns associated with disrupted services during emergencies;

-

waterborne illness associated with water scarcity, flooding, storm surge, etc.; and,

-

vector, air quality, and water contamination concerns associated with solid waste management.

Sample Locations

Alaska

Health and Culture Adaptation Options, September 2009, HC2: Surveillance and Control (link)

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Public health strategy 4 (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Climate Change Advisory Task Force, Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation E.2 (link)

3. Community Health Impact Assessments

Link to Public Health

Screen proposed climate change adaptation and mitigation activities for direct and indirect public health benefits and harms. For example, incorporate climate change adaptation screening into Environmental Impact Assessments. Prioritize activities that promote resilience and minimize direct and indirect harm to public health, the environment, and the economy.

Sample Locations

Alaska

Health and Culture Adaptation Options, September 2009, HC3: Community Health Impact Evaluation Initiative (link)

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Key recommendation 8 (link)

Florida

Energy and Climate Change Action Plan: Phase 2, 2008, ADP-2: Comprehensive Planning and ADP-11: Organizing State Government for the Long Haul (link)

4. Adapt community sanitation and solid waste management to respond to a changing climate.

Link to Public Health

Sanitation and solid waste systems may be compromised by a warming climate:

-

Melting permafrost in northern regions can lead to subsidence, causing structural rupture of sanitation systems.

-

Storm surges and flooding can compromise water treatment plants and sanitary sewers.

-

Drought can compromise source water quantity and quality.

-

Vectors and pests may extend their range into areas not prepared for them due to warming ambient temperatures

Sample Locations

Alaska

Health and Culture Adaptation Options, September 2009, HC4: Sanitation (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Climate Change Advisory Task Force, Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation F.2 (link)

King County, Washington

2008 King County Climate Report: Land Use, Buildings and Transportation Infrastructure (link)

New York City

plaNYC 2007, Climate Change Initiative 1: Create an Intergovernmental Task Force to Protect Our Vital Infrastructure (link)

5. Consider adaptation strategies and/or avoid development in areas at risk to climate-related hazards, such as flooding, wildfires, erosion, subsidence, etc.

Link to Public Health

Developments that are vulnerable to climate change are also vulnerable to accompanying public health risks, such as drowning, heat stroke, waterborne disease, etc. Many public health crises can be avoided by prohibiting development in vulnerable areas and by incorporating community resilience into planning requirements.

Sample Locations

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Key recommendations 3 & 5 (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Climate Change Advisory Task Force, Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation C.1, D.4, E.1 (link)

New York City

plaNYC 2007, Energy Initiative 3: Strengthen energy and building codes for New York City (link)

6. Institute comprehensive water management policies.

Link to Public Health

Water quality can be protected through efficiency measures, protecting water sources, and supporting ecosystem resilience in the areas that supply water.

Water supplies may need to be drawn from new sources to meet demand, such as rainwater, on-site wastewater treatment, and municipally reclaimed water. Public health considerations should be incorporated into the regulations governing these new technologies to protect the public from exposure to waterborne diseases.

Sample Locations

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Key recommendation 2 (link)

Colorado

Climate Action Panel, 2007 Report, WA 1-WA 14 (link)

Florida

Energy and Climate Change Action Plan: Phase 2, 2008, ADP-4: Water Resources Management (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Climate Change Advisory Task Force, Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation D.4, D.5, D.7 (link)

King County, Washington

2008 King County Climate Report: Surface Water Management, Freshwater Quality and Water Supply (link)

7. Incorporate climate change risk into emergency preparedness, hazard mitigation, and response plans.

Link to Public Health

Incorporating public health surveillance data into regional climate change models will help emergency responders prepare for short- and long-term shifts in the type and intensity of climate-related events.

Sample Locations

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Key recommendation 10, Comprehensive state strategy 3, Public health strategy 5 (link)

Florida

Energy and Climate Change Action Plan: Phase 2, 2008, ADP-8: Emergency Preparedness and Response (link)

King County, Washington

2008 King County Climate Report: Flood control (link)

New York City

plaNYC 2007, Initiative 3: Launch a Citywide Strategic Planning Process for Climate Change Adaptation (link)

8. Inform, educate, and empower the public about the links between health and climate change.

Link to Public Health

Community engagement is one of the 10 essential services of public health. Many of the topics that form part of traditional public health educational outreach are also connected with climate change: extreme heat, winter weather, flooding, air quality (asthma, allergies, etc.), exposure to toxic chemicals, etc. A climate change public education and engagement program should build off of these longstanding public health concerns to establish links between individual behavioral changes and climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Sample Locations

California

2009 Climate Adaptation Strategy, Public health strategy 2 (link)

Florida

Energy and Climate Change Action Plan: Phase 2, 2008, ADP-14: Education (link)

Miami-Dade County, Florida

Climate Change Advisory Task Force, Second Report and Initial Recommendations, 2008, Recommendation E.3, F.1, F.5, F.6 (link)

New York City

plaNYC 2007, Climate Change Initiative 2: Work with Vulnerable Neighborhoods to Develop Site-Specific Strategies (link)

The next installment of this post will review mitigation activities that fall within the traditional role of sustainability.

Suggested Additional Reading

Center for Climate Strategies, http://www.climatestrategies.us/

King County, Washington

Preparing for Climate Change: A Guidebook for Local, Regional, and State Governments, 2007, http://cses.washington.edu/cig/fpt/guidebook.shtml

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, http://www.ipcc.ch/

Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report, http://www.ipcc.ch/pdf/assessment-report/ar4/syr/ar4_syr.pdf

Pew Center on Global Climate Change, http://www.pewclimate.org

Adaptation, http://www.pewclimate.org/hottopics/adaptation

Energy Efficiency , http://www.pewclimate.org/energy-efficiency

Copyright: © Biositu, LLC, and Building Public Health, 2010.

Background Reading on Climate Change and Public Health

This post outlines suggested reading on public health issues associated with climate change. I will update it as new reports and studies are released.

The CDC Climate Change website suggests the following papers as a broad foundation on the health effects of climate change:

Frumkin H, Hess J, and Vindigni S. Peak petroleum and public health. JAMA. 298:1688-1690, 2007.

Frumkin H, Hess J, Luber G, Malilay J, and McGeehin M. Climate Change: The Public Health Response. Am J Public Health. 98:435-445, 2008.

Luber G, and Hess J. Climate change and human health in the United States. J of Env Health. 70(5):43-44, 2007.

Patz JA, McGeehin M, Bernard SM, Ebie KL, Epstein PR, Grambsch A, Gubler DJ, Reiter P, Romieu I, Rose JB, Samet JM, Trtang J. The potential health impacts of climate variability and change for the US. Env Hlth Pers. 108 (4): 36-54, 2000.

CDC is also launching a webinar series titled “Climate Change: Mastering the Public Health Role.” For more information, visit the Climate Change and Public Health Workforce Development web page.

Additional general resources:

Climate Change: Our Health in the Balance, American Public Health Association 2008 National Public Health Week Partner Toolkit

The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) convened a series of webinars in 2008 and 2009 focused on the public health impacts of climate change: http://www.astho.org/Programs/Environmental-Health/Natural-Environment/Climate-Change-and-Public-Health/

Trust for America’s Health released an issue report in October 2009 highlighting climate change activity to date both at the federal level and by state and local health departments: Health Problems Heat Up: Climate Change and the Public’s Health

The U.S. Climate Change Science Program and the Subcommittee on Global Change Research released the following report on the health effects of global change in 2008: Analyses of the Effects of Global Change on Human Health and Welfare and Human Systems

The World Health Organization has released a training course on climate change and health targeted to public health professionals: Protecting our Health from Climate Change

Copyright: © Biositu, LLC, and Building Public Health, 2010.

A Healthy Climate

With negotiations in Copenhagen only days away, healthcare insurance reform under active discussion, and cap and trade legislation the next big ticket item on the U.S. Congressional agenda, it seems appropriate timing to broaden the climate change debate to include its public health consequences.

Global authorities such as the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the World Health Organization, and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change have identified climate change as a significant emerging threat to public health worldwide.

Why?

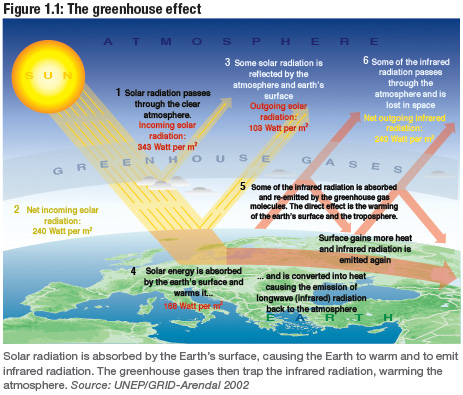

Climate scientists have found that Global Warming, the tendency of the Earth to warm when certain gases accumulating in the atmosphere prevent solar radiation from escaping out to space after bouncing off of the Earth’s surface, will cause (and has probably already started causing) increased temperature and increased frequency and severity of extreme weather events such as hurricanes, drought, extreme heat, and flooding.

2009 Climate Change Science Compendium. Ed. Catherine P. McMullen. UNEP, September 2009. Figure 1.1. p. 4.

The following table, "Anticipated Health Effects of Climate Change in the United States,” adapted from Frumkin et al., Am J Public Health (2008); 98:435-445, outlines the likely health effects and associated vulnerable populations associated with a changing climate.

|

Weather Event |

Health Effects |

Populations Most Affected |

|

Heat waves |

Heat stress |

Very old Athletes Socially isolated Poor Respiratory disease |

|

Extreme weather events |

Injuries Drowning Mass population movement International conflict Mental health |

Coastal, low-lying land Poor Children Displaced Depression/anxiety General population |

|

Winter weather anomalies |

Slips and falls Motor vehicle crashes |

Northern climate dwellers Elderly Drivers |

|

Sea-level rise |

Injuries Drowning Water and soil salinization Ecosystem disruption Economic disruption |

Coastal dwellers Low SES |

|

Increased ozone and pollen formation |

Respiratory disease exacerbation (e.g. COPD, asthma, allergic rhinitis, bronchitis) |

Elderly Children Respiratory disease |

|

Drought – ecosystem migration |

Food and water shortages Malnutrition |

Low SES Elderly Children |

|

Drought, flooding, increased mean temperature |

Food- and waterborne disease Vector-borne disease |

Swimmers Outdoor workers Outdoor recreation Poor Multiple other populations |

So, why is public health largely excluded from climate change policy?

Climate change policies such as the Kyoto Protocol and non-binding challenges such as U.S. Council of Mayors Climate Protection Agreement have focused largely on encouraging energy efficiency measures and boosting renewable energy capacity for two reasons:

1. They appear to directly address the problem: too many human-generated greenhouse gas emissions; and,

2. They reduce a complex, global crisis into a two, easily digestible strategies.

The problem with this strategy has been that it robs the climate change crisis of immediacy. The average person or company does not “see” the tangible benefits of reducing energy consumption and purchasing renewable energy. Their small contribution will not change the world’s climate in a readily noticeable way, and it probably will not even change the microclimate around an individual house or business unless the activity is coordinated into a neighborhood or district level, as advocated by the Living Building Challenge through the concept of “Scale Jumping.”[1]

Energy efficiency saves money up front to a point, but the cost-benefit analysis for an energy efficiency strategy loses its appeal after the obvious measures have been implemented (e.g., changing to energy efficient light bulbs, etc.) – unless another value proposition is overlaid that brings immediacy and another order of magnitude to the enterprise.

This column will tease out that value proposition by uncovering the links between public health and climate change policies and practices. It will place particular emphasis on economic co-benefits and the power of a health message to build political will and influence behavioral change.

Copyright: © Biositu, LLC, and Building Public Health, 2010.

[1] “Scale Jumping” is defined by the Living Building Challenge as “the implementation of solutions beyond the building scale that maximize ecological benefit while maintaining self-sufficiency at the city block, neighborhood, or community scale.” Source: http://ilbi.org/the-standard/lbc-v1.3.pdf, footnote 14, p. 11.